THE GLASS COFFIN: The Beothuk Man and Child Newfoundland Tried to Forget

They were once the most unforgettable sight in a Newfoundland museum. A baby—curled in the fetal position, tiny bones wrapped in birchbark and caribou skin. A towering man—strung together from stolen bones, looming six-foot-six in a glass case. For nearly 100 years, schoolchildren filed in to stare. And then one day… the exhibit vanished.

But this isn’t just about a creepy museum display.

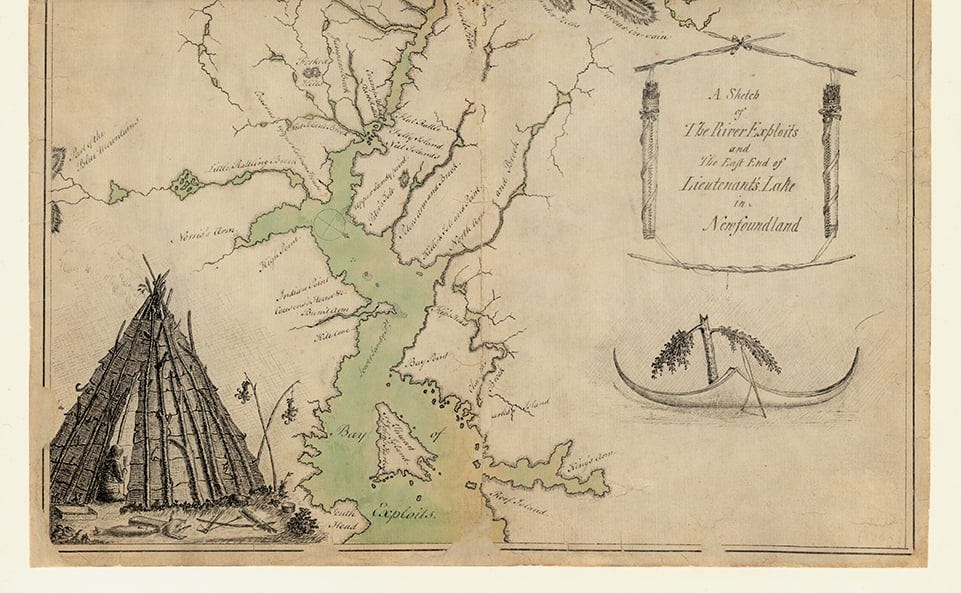

It’s about the Beothuk—the Indigenous people of Newfoundland who lived here long before European settlers arrived. They were known for their red ochre body paint, their coastal lifestyle, and their determination to avoid contact with outsiders. But contact came anyway—in the form of disease, starvation, and colonial violence. By 1829, the last known Beothuk, a woman named Shanawdithit, died in St. John’s. Officials declared the entire culture extinct.

What they didn’t tell you is that their bones were never laid to rest.

They were put in glass boxes.

And left to haunt the halls of a forgotten museum.

Dug Up, Dried Out, and Put on Display

In 1886, a child’s grave was discovered on a remote island off Notre Dame Bay. The grave was delicate. Intentional. The little girl’s body was curled up in a fetal position, wrapped in birchbark and caribou hide, laid to rest with a necklace, tiny toy canoes, a miniature bow, dried fish, and beads.

The child’s body was exhumed and shipped to St. John’s. She was stripped of her burial wrappings, placed on a plank, and put in a glass box at the Newfoundland Museum on Duckworth Street.

A year later, in 1888, the body of a man—nearly 6'6" tall—was found in a seaside cave on Comfort Island. A fisherman named George Hodder sold his skeleton to the museum.

They posed him upright.

Laced his joints together.

Hung him like a colonial marionette.

Together, they became known as “The Beothuk Man and His Baby”—the star attraction in what locals now remember as “the old museum with the bones.”

“The skeletal remains of both individuals were displayed until the late 1970s when evolving standards in museum ethics and Indigenous rights prompted their removal from public view.”

— [ATIPP Document, p.1 - See docs linked at bottom of post]

Childhood Horror Show

Ask any Newfoundlander who visited before 1980, and they’ll tell you the same thing:

They remember that room.

The child’s body, impossibly small and real.

The man, looming like a sentinel behind yellowed glass.

Some claimed you could still see dried skin on the child’s knees.

Others remember a doll—tucked beside her ribs like a haunting love letter.

“It was the seemingly petrified child folded up into itself that made the big impression... The face was partially visible… as were the legs and feet.”

— Visitor recollection, 1960s

One boy said he thought they ruled the museum.

Another swore the bones in the man’s hands moved between visits.

Gone Without a Trace

Then—sometime around 1976—the exhibit disappeared.

No announcement. No replacement. No explanation.

Just empty glass cases.

Rumors swirled:

The bones had been cursed.

A staff member had nightmares so vivid she refused to return to work.

The child’s glass case cracked—twice—in the same week.

But behind the scenes, the truth was more chilling than any ghost story:

“There have been internal discussions regarding appropriate stewardship of Indigenous remains, but no formal consultation has taken place with Indigenous groups regarding the Beothuk child and adult currently in government possession.”

— [ATIPP Document, p.1]

They didn’t vanish.

They were buried again—this time in a drawer.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newfoundland History Sleuth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.