Nazis in Newfoundland: The Strange Case of Smallwood’s Shadow

Picture this: Newfoundland in the 1950s, still adjusting to joining Canada, is buzzing with plans for modernization. Enter a man with a shady past, big promises, and even bigger secrets—a refugee from Europe with ties to the Nazis. This isn’t the opening of a spy thriller; it’s the real-life story of Alfred Valdmanis and Newfoundland’s peculiar brush with Nazi-era intrigues.

The Cast of Characters

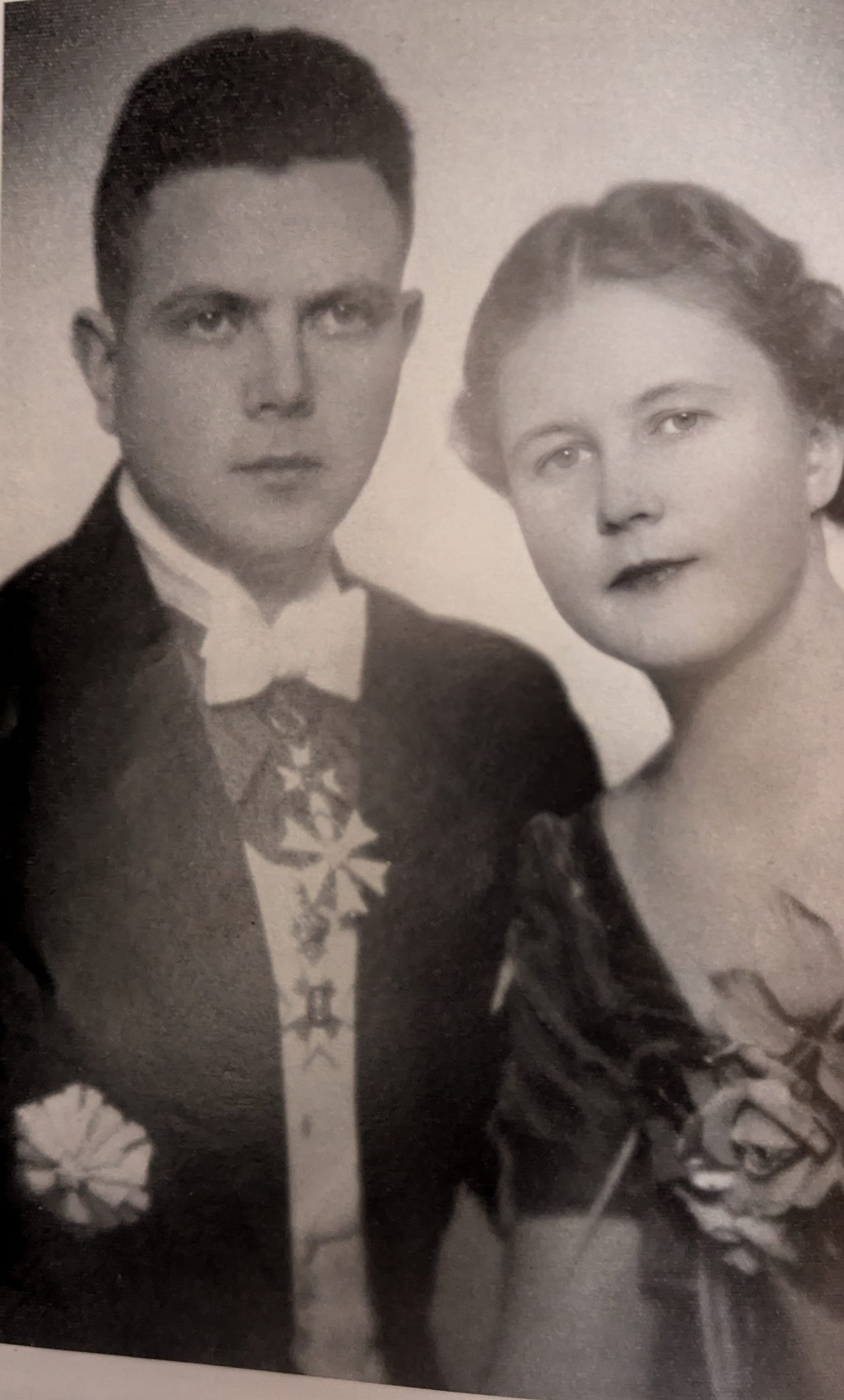

Let’s start with Joey Smallwood, Newfoundland’s first premier, known for his vision of transforming the province into an industrial powerhouse. Smallwood’s ambitions led him to hire Alfred Valdmanis, a Latvian economist with a flair for making deals—and enemies. Valdmanis claimed to have escaped the chaos of post-war Europe with a solid reputation and experience as Latvia’s finance minister. What Smallwood may not have fully realized was that Valdmanis’s resume came with a shadow: allegations of war crimes and connections to the Nazi regime.

Valdmanis fled Europe after Latvia fell under Soviet control. During the war, he had cozied up to German authorities, allegedly helping facilitate Nazi policies in occupied Latvia. Some reports even tied him to the mass murder of Jews, a connection that would resurface in damning allegations years later. By the time Valdmanis landed in Newfoundland in 1948, he carried not only a suitcase but also a $10,000 nest egg—a suspiciously tidy sum for a displaced person.

Smallwood, enamored by Valdmanis’s credentials and smooth talk, gave him free rein to attract German industries to Newfoundland. Valdmanis set up shop in the Colonial Building, rubbing elbows with Newfoundland’s elite and securing deals to establish companies like North Star Cement. He demanded the highest salary on the public payroll—$10,000 a year, far above Smallwood’s own $7,000. And when he asked for a raise to $25,000, he got it.

From Latvia to Newfoundland

Valdmanis fled Europe after Latvia fell under Soviet control. During the war, he had cozied up to German authorities, allegedly helping facilitate Nazi policies in occupied Latvia. Some reports even tied him to the mass murder of Jews, a connection that would resurface in damning allegations years later. By the time Valdmanis landed in Newfoundland in 1948, he carried not only a suitcase but also a $10,000 nest egg—a suspiciously tidy sum for a displaced person.

Smallwood, enamored by Valdmanis’s credentials and smooth talk, gave him free rein to attract German industries to Newfoundland, despite warnings from some in his administration who questioned Valdmanis’s background and his bold promises. Critics pointed out inconsistencies in Valdmanis’s past and raised concerns about his growing influence, but Smallwood, focused on his vision for modernization, dismissed these reservations as unfounded skepticism. Valdmanis set up shop in the Colonial Building, rubbing elbows with Newfoundland’s elite and securing deals to establish companies like North Star Cement. He demanded the highest salary on the public payroll—$10,000 a year, far above Smallwood’s own $7,000. And when he asked for a raise to $25,000, he got it.

A Legacy of Corruption

Valdmanis’s time in Newfoundland was marked by scandals. He was accused of pocketing kickbacks from German companies, laundering money through mysterious “foundations,” and using his secretary as a private courier to send cash-stuffed packages to his wife in Montreal. His legal troubles didn’t stop there. In 1952, he tried to shake down the Rothschilds for $1 million in exchange for lumber and mineral rights in Labrador. Spoiler alert: it didn’t work.

Even his allies began to turn against him. Harold Horwood, a cabinet member under Smallwood, later described Valdmanis as a man immune to criticism who wielded immense power over the premier. This power, it seemed, stemmed from a combination of Smallwood’s deep trust in Valdmanis’s abilities, his bold promises of industrial prosperity, and possibly even the premier’s inability—or unwillingness—to fully confront the darker aspects of Valdmanis’s past. Valdmanis’s charm, coupled with his connections to powerful German industrialists, gave him an aura of indispensability that Smallwood could hardly ignore, even as controversies mounted. He dismissed ministers who opposed him and operated as if Newfoundland were his personal fiefdom.

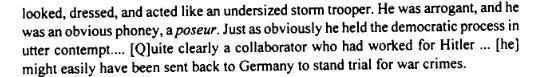

Harold Horwood who was on Smallwood’s cabinet stated:

The Nazi Allegations

In 1951, The Jewish Weekly dropped a bombshell: it alleged that Valdmanis had been complicit in the Nazi occupation of Latvia, even helping organize the deportation and murder of Jews. These accusations cast a dark shadow over Newfoundland’s government. While Valdmanis denied the allegations, the optics were terrible. Imagine a province trying to shed its reputation as Canada’s poorest region, only to discover its star economic advisor had skeletons—literal and figurative—in his closet.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newfoundland History Sleuth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.