Death at the Barn Dance: The Knights of Columbus Hostel Fire – Newfoundland’s Wartime Cover-Up?

99 Dead. Radio Silence. And a Whole Lot of Government Shrugs

Picture this: it’s a snowy wartime Saturday night in St. John’s. Your ration book is half-used, your blackout curtains are drawn, and everyone you know is packed like sardines into the Knights of Columbus Hostel to hear live music, flirt with a few soldiers, and forget—for one night—that the world is literally on fire.

Enter: Uncle Tim’s Barn Dance, broadcasting live across Newfoundland. The fiddle’s hot. The crowd’s hotter. Then—BOOM.

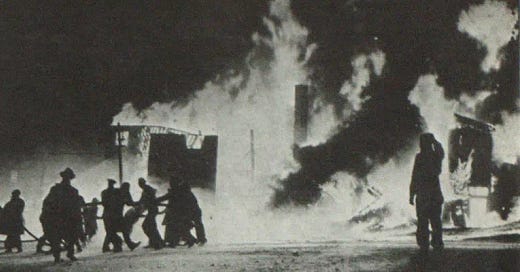

Within minutes, the building is an inferno.

Ninety-nine dead. Bodies charred. Smoke rising above the harbor. And all the government gave us? Silence. A plaque. And an inquiry that asked just enough questions to shut everyone up.

The K of C Hostel: Built for Comfort, Designed for Catastrophe

Let’s start with the building itself.

Constructed in 1941, the Knights of Columbus Hostel cost $100,000—a luxurious morale booster for the war effort. It had a restaurant, recreation room, dormitories, and an auditorium for events like the now-infamous barn dance. Sounds nice, right? Well, here’s the kicker:

Blackout laws meant every window was covered with thick, nailed-down curtains.

The doors opened inward. In a panic, people crushed themselves trying to escape.

There were no fire escapes.

No sprinkler system.

You don’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to see where this is going.

Witnesses said the fire started in the attic. A smoldering ember, maybe from faulty wiring or a cigarette, burned quietly above the crowd. When someone opened the attic door to investigate—boom. Flashover. The entire top floor ignited. Within 3.5 minutes, the building was an oven.

Soldiers broke windows with their bare fists. People jumped from the second floor. Some survivors described “smoke so thick you couldn’t see your own hands.” Others remembered screaming. Burning flesh. Cracking wood.

Uncle Tim’s Barn Dance, mid-broadcast, cut to static. No sign-off. No explanation. Just silence.

The "Official" Story: Too Fast, Too Convenient

Immediately after the fire, government officials rushed to control the narrative.

No public inquiry.

No criminal investigation.

No enemy sabotage.

No blame.

Just "tragic accident" — case closed.

The survivors?

They remembered things differently.

“The fire was too fast. Too powerful. Like someone threw gas on it.”

— A survivor, quoted anonymously years later.

Witnesses described doors mysteriously chained shut and military men acting strangely near the rear entrance shortly before the flames exploded across the dance floor.

The city mourned, and the world moved on.

Except for a few who knew there was something wrong.

Bren Walsh: The Journalist Who Got Too Close

Enter Bren Walsh — one of Newfoundland’s most legendary journalists.

He wasn’t content with the headlines.

He started digging. Quietly. Methodically.

Decades after the fire, Walsh compiled interviews, whispered confessions, military rumors — everything that didn’t fit the official version.

According to Walsh’s sources, the fire was not an accident. It was set deliberately by an American serviceman. A pyromaniac stationed at nearby Fort Pepperrell.

According to off-the-record testimony collected by Walsh:

The U.S. military knew about the soldier’s mental instability.

He had previous incidents of setting fires, covered up internally.

The night of December 12th, 1942 — in a moment of madness or twisted compulsion — he set fire to the hostel.

The fire grew out of control almost instantly — accelerated by flammable decorations and the building’s aging wooden structure.

Walsh’s notes allegedly described how the soldier was immediately removed from Newfoundland after the fire — secretly shipped back to the U.S., diagnosed as mentally unfit, and hidden away.

The Cover-Up: Why the Truth Had to Die

In 1942, Newfoundland wasn’t part of Canada yet. It was still a British colony, barely holding itself together under the strain of World War II.

The Americans had landed on Newfoundland’s shores with their money, their soldiers, their bases — and their political power.

If news had broken that an American had slaughtered almost 100 people, it would have been catastrophic:

Anti-American riots.

Breakdown of vital wartime alliances.

Loss of Newfoundland’s fragile trust in Britain and Canada.

The Americans quietly paid out secret compensation to some families.

The rest were left with "official condolences" and half-explanations.

Newfoundland’s history moved on — without the full story ever being told.

Here’s where it gets even more frustrating:

Walsh never published his findings.

He died before he could.

His papers — the interviews, the names, the hard evidence — disappeared.

Some say his family destroyed the files to avoid trouble.

Others whisper that government officials pressured them into silence.

Today, only fragments remain — old rumors, half-remembered quotes, locked-up archives.

The truth is still out there.

But like the ashes of the hostel, it’s buried deep.

Enter the Inquiry: Justice Dunfield and the Art of the Neat Little Bow

The Newfoundland government appointed Justice Brian Dunfield to head the investigation. He was handed 174 witnesses, a torched ruin of a building, and public outrage that couldn’t be soothed with church bells and flower wreaths.

His report? A real page-turner. Poor ventilation. Inward-opening doors. Blackout curtains. Panic. Construction flaws.

A Series of Totally Unrelated Fires (Insert Sarcasm Here)

Let’s review the timeline:

December 8, 1942: A suspicious fire at the YMCA Hostel.

December 10, 1942: Fire guts the Old Colony Club. Four dead.

December 12, 1942: K of C Hostel burns. Ninety-nine dead.

December 13, 1942: Attempted arson at the U.S.O. Club.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newfoundland History Sleuth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.